It is difficult to fully capture all the ways that Black wealth in Atlanta has been impacted by the structural determinants. But stakeholders committed to building Black wealth should not limit their analysis to typical measures of financial health to understand and rectify past harms that intersect with Black wealth outcomes. For this reason, we extend our focus to other less-discussed determinants of Black wealth: mass incarceration, access to climate resilient communities, a fair tax code, and a free democracy.

Freedom from Mass Incarceration and Overpolicing

The history of policing and incarceration is inextricably linked to today’s wealth outcomes. The combined effects of mass incarceration permeate the lives of people directly subjected to interactions with law enforcement and imprisonment, and ripples throughout the lives of their friends, family members, and entire communities. Contact with the mass incarceration system severely limits wealth building opportunities. For example, states with high incarceration rates are associated with fewer Black homeownership rates,109 which increases the racial wealth divide. This is important to consider for Atlantans who just so happen to live in a state that has the highest rate of carceral control in the country.110

The physical, mental, and social costs of contact with the criminal legal system is significant in Atlanta’s Black communities, but so is the financial cost. In 2022, the City of Atlanta spent $292.3 million on carceral activities – about $589 per resident – which includes spending on corrections and community services, police, and the citizens review board. The total spent on carceral systems represents roughly 14 percent of the city’s budget.111

Racial discrimination in the criminal legal system compounds poor wealth outcomes that Black Atlantans already face while reinforcing racial wealth inequality. For instance, the median wealth of formerly incarcerated white adults is higher than the median wealth of Black adults who had never been incarcerated before.112 The disproportionate lack of wealth means Black residents have fewer resources available to navigate the system with high-quality lawyers and investigators and post bond for timely release from jail.

Arrests and convictions have a sharp impact on wealth building prospects for Black households. In recent research, arrests were found to matter most for wealth outcomes. Even arrests without conviction is associated with wealth declines – wealth is reduced to little or nothing while in jail or prison.113 Attention to the relationship between arrests and Black Atlantans is critical given the reality that Black people account for an egregious 90 percent of all arrests made by the Atlanta Police Department, despite making up just 48 percent of the city’s population.

Due to oppressive public policies, overpolicing, and an excessive use of incarceration, the relationship between wealth and arrests in Atlanta is clear. In 2022, a study found that a third of people incarcerated in Fulton County Jail were there because they couldn’t pay a bond of $15,000 or less. The study reported that one individual spent nearly 500 days in jail because he couldn’t afford his freedom.114

The high number of arrests is associated with increased fines and fees imposed on Black communities, which can drive Black households deeper into debt and reverse or completely eliminate opportunities to build wealth altogether. Despite fines, fees, and cash bail systems being rooted in systems of control that emerged from enslavement, the City of Atlanta continues to enforce these policies disproportionately among Black residents, actively contributing to the city’s massive racial wealth divide. To that end, addressing the mass incarceration and overpolicing of Black Atlantans is a key community wealth building strategy.

Freedom to Participate in Democracy

Wealth inequality and financial insecurity has as much an effect on suppressing democracy as draconian poll taxes, poll closings, and voter ID laws. Atlanta’s stubborn racial wealth divide presents a loss of a lever of power for Black communities to remove barriers to building wealth by electing leaders or holding incumbents accountable to address their specific needs and improve their access to opportunities.

As the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement, Atlanta has long been in the voting rights spotlight as a result of a notable history of organizing, Black political power, and advances in voting rights. Atlanta’s contributions to the national movements that led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 cannot be understated. For example, both reforms were driven in large part by the organizing of the Atlanta Student Movement.115 Atlanta played a critical role in securing the rights of Black Americans and improving the state of democracy in the United States.

Today Atlanta is at a crossroads when it comes to voting rights in the 21st century. Recent historic elections have shone a bright light on the City of Atlanta and Fulton County, which played an outsized role in ensuring a changing political regime in the 2020 presidential and senate elections.116 In response to this, efforts to limit the voting power of Black Atlantans and other Black residents across the South were launched in the form of racially biased voter suppression tactics, such as improper voter purges and the closing of polling locations in Black neighborhoods. For example, state lawmakers passed a law in 2021 that reduced the availability of voting drop boxes in Black communities across Greater Atlanta from 107 to just 25.117

It is not a coincidence that Atlanta’s wealth and income inequality has grown as democracy has become increasingly exclusionary. In order to build Black wealth, Atlanta must prioritize full democratic participation in processes that determine economic outcomes in across the city.

Capital Gains, Inheritances, and Tax Advantages

Since the 1980s, the racial wealth divide has widened as capital gains have predominantly benefited white households.118 While the national Black-white income gap has narrowed over time, differences in Black and white Americans’ capital gains rates throughout history have accelerated the chasm between Black and white wealth, resulting in an enduring wealth divide that shows no sign of resolving. Meanwhile, the City of Atlanta’s income divide continues to grow, offsetting any possibility of Black households to reap the benefits of capital gains at a rate similar to that of white households.

Wealth Transfers

While local Atlanta data on investment assets does not exist, we can see how the disparities play out at the national level. White families make up 65 percent of families but own nearly 90 percent of corporate stock, nearly 90 percent of private business assets, and more than 76 percent of real estate holdings. Black families, in contrast, own just 1.1 percent of corporate equities, less than 2 percent of private business assets, and under 6 percent of real estate holdings.119 We can, therefore, assume that white families receive a disproportionate share of the income and wealth generated by capital gains, which helps to explain the widening racial income divide in Atlanta.120

Holdings in various investment assets allows families to pass down ownership of the assets from generation to generation, thus accruing financial returns that will sustain the long-term financial well-being of families. Recent studies show that half of total wealth in the United States results from intra-generational transfers from inheritances. Moreover, these inheritances now account for more of the racial wealth divide than any other demographic and socioeconomic indicators including education, income and household structure.121

Local data is also unavailable on the rate of generational transfers and inheritances, but nationally, 30 percent of white households receive an average inheritance of about $195,500 compared to 10 percent of Black households that receive an average inheritance of $100,000.122 Because investment assets and inheritances are lightly taxed, these inequities can play a large role in perpetuating a widening Black-white wealth divide in Atlanta that will span generations.

A Fair Tax Code

While some may argue the tax code is race neutral, the data tells a different story. The tax code benefits wealth over work by taxing income from ownership at much lower rates than income from salaries and wages, which is the primary source of income for Black households. As a result, Black households are less likely to reap the wealth building benefits from the tax code given the inequities in income and investment assets.

City-level data on taxes is not available, but state-level data exists, showing the regressive and inequitable nature of the tax code in Georgia. Georgia’s income tax contains a design flaw that causes it to fall more sharply on workers with low-income. Georgia’s income tax brackets are mostly unchanged from the 1930s, when $10,000 a year was considered a high-wage salary. As a result, the state’s income tax starts applying to families at unusually low levels of income.

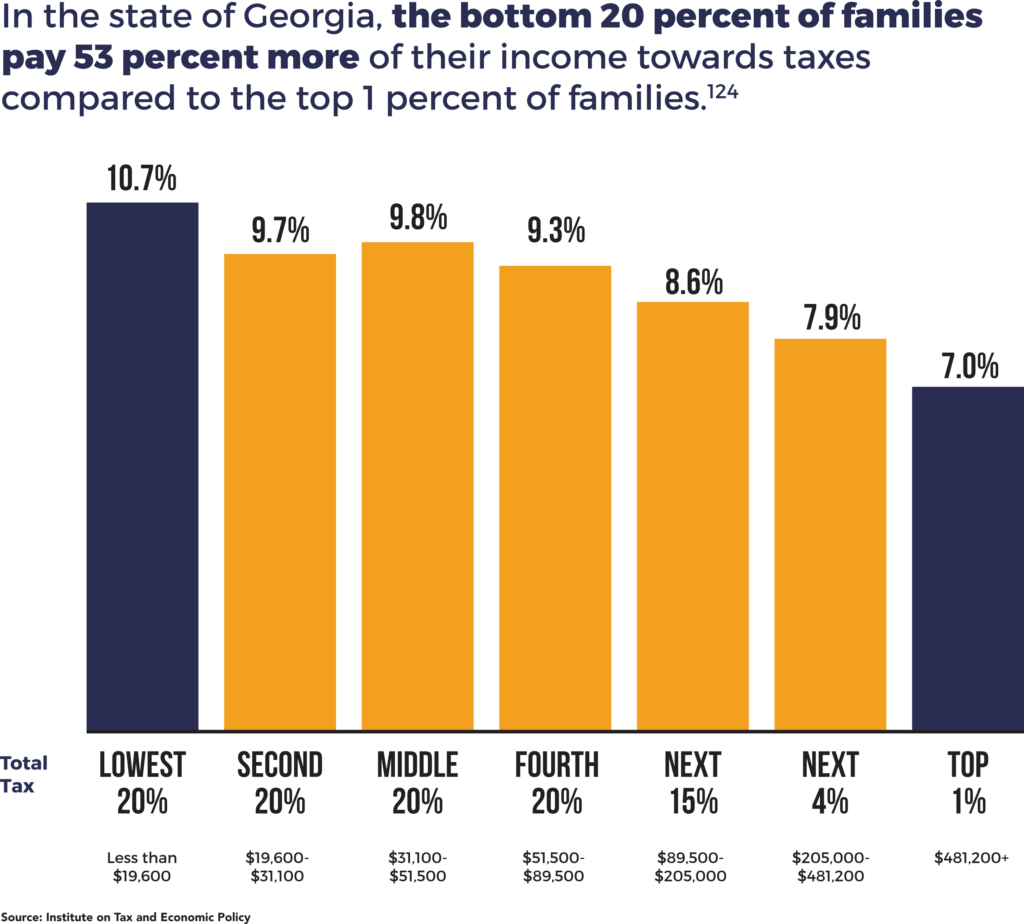

In 1990, Atlanta families with an income of $50,000 and less — disproportionately Black families — spent about 10 percent of their income on state and local taxes. Meanwhile, families with an income of $100,000 and more spent less than one percent of their income on state and local taxes.123 Today in Georgia, the 20 percent of families with the lowest income pay 11 percent of their income towards taxes, while the top one percent of families with the highest income pay seven percent.

Getting Local: Atlanta Property Taxes and Wealth

For the 33 percent of Black homeowners in Atlanta, the tax advantages for property ownership still amounts to a racial subsidy for white families, while local property tax assessments are systematically biased against Black homeowners. For instance, Atlanta and Fulton County have a history of overtaxing Black property. The county has continued a racially biased practice of valuing Black-owned properties with a significant share of Black residents at lower amounts than their white counterparts.

Nationally, Black homeowners pay higher property taxes than white homeowners, even while appraisers are more likely to assign them with lower home values. This practice created a pattern of increasing property tax delinquency among Black homeowners.

As a result, property taxes lead to losses of wealth in Atlanta disproportionately for Black homeowners. A recent investigative study analyzed more than 3,200 properties auctioned for delinquent tax debt between 2015 and 2022 in Fulton County and found that 80 percent were in historically Black neighborhoods.125

Without property tax relief, primarily in the form of homestead exemptions in these cases, Fulton County will not offer payment plans to help homeowners settle their debt. In fact, it has been reported that Fulton County denies people who should otherwise be eligible for exemptions and other forms of property tax relief. Unfortunately, if families can’t pay their tax bills, Fulton County can sell their debt to for-profit investors who can in-turn auction off their homes.126

While we need better data to understand the role of capital gains and tax advantages in reinforcing the racial wealth divide in Atlanta, the insights provided above do shine a light on critical policies and practices that warrant attention. If Atlanta policymakers want to help build Black community wealth, eliminating disparities in access to investment assets and addressing racial disparities cemented by the tax code will be essential.

Access to Climate Resilient Communities and Wealth

A largely ignored contributor to the racial wealth divide is climate change and related natural disasters. For instance, damages from natural hazards, which are expected to increase substantially in coming years, are found to increase wealth inequality.127 As we look to solutions to build Black wealth, we must consider the impending harms that will be created by climate change that are compounded by generations of environmental racism in Atlanta.

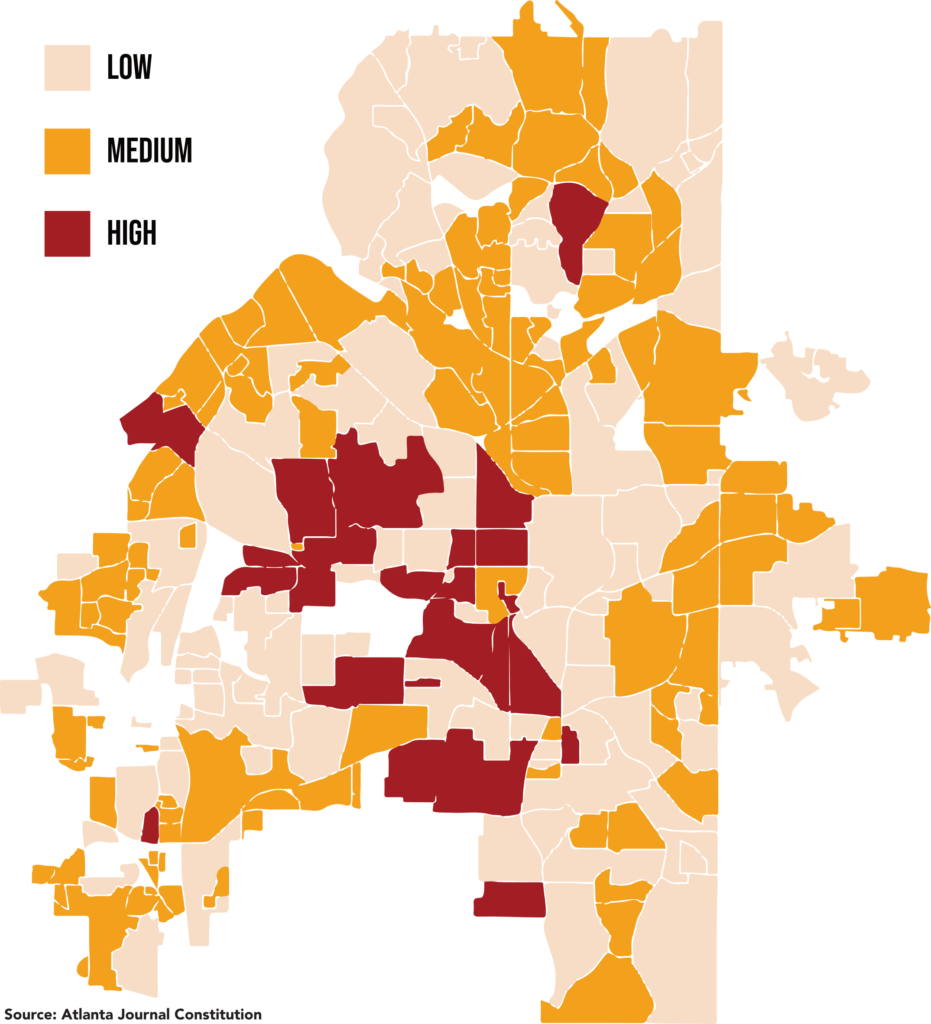

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) developed the Environmental Justice Index (EJI) to assess the ability of neighborhoods and cities to respond to environmental hazards or to be resilient in the face of climate shocks and stressors. The EJI for majority Black neighborhoods is 90 percent compared to the overall city average of 62 percent. In other words, majority Black neighborhoods in Atlanta are 28 percentage points more vulnerable to environmental shocks compared to the rest of the city.128 The widening racial wealth divide in Atlanta means that Black families are more likely to live in communities that are more vulnerable to environmental threats.

Another factor that bridges wealth and climate is rising heat. Across Atlanta, substandard housing can lead to poor health outcomes for households and the costs to maintain and keep housing safe and cooled can be significant. A recent study of rising heat in Atlanta’s neighborhoods found that 30 percent of houses in Atlanta’s historically Black Pittsburgh neighborhood lack central heating and air cooling systems. In fact, most neighborhoods that were found to have the highest heat vulnerability are majority Black neighborhoods.129

Extreme heat is also linked to higher utility costs. It costs households money to keep the air conditioning running, but Black households bear the brunt of these costs more than others. At 9.5 percent, Black households in Atlanta experience double the energy burden of the average household (4.7 percent).130

The growing threat of climate change heat requires all policy leaders to take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to pursue policies that mitigate the effects of extreme heat, natural disasters, and the financial stress these events cause. These efforts are necessary across all of Atlanta, but especially in low-income neighborhoods, communities of color, and other settings where the structural and financial impacts of climate change are felt the greatest.