Homeownership is often recognized as the long-term goalpost for Americans to strive toward on their journey to build wealth. Homeownership offers families the needs and comforts of shelter, but it can also function as an asset that can be used to transfer generational wealth, build equity, and access alternate forms of capital for economic mobility. The goalpost, however, is not equidistant for all racial-ethnic groups within Atlanta, as the pathway to homeownership is fraught with harmful policies, prejudice in the housing market, and predatory financing for Black people. Moreover, homeownership is not the driver of the racial wealth divide that conventional wisdom leads us to believe.79

A Brief Backstory:

United States v. Decatur Federal

The Black residential population of Atlanta, akin to many southern cities, endured systemic and coordinated efforts by financial institutions, mortgage lenders, insurance companies, and land developers to prevent wealth building in the form of homeownership.80 The most well-known of these coordinated efforts is redlining – a discriminatory practice whereby credit lending institutions and developers withhold investment in specific neighborhoods, often comprised of majority residents of color.81 The coordinated efforts by these groups have restricted Black Atlantans from obtaining fair mortgage rates, accessing affordable and adequate insurance coverage for their homes, migrating into various parts of the city, and participating in the wealth-building activities afforded to homeowners.82 The pervasive presence and impacts of redlining in Atlanta are clearly outlined in the 1992 landmark mortgage lending case, United States v. Decatur Federal Savings and Loan.

The United States v. Decatur Federal was the first case where the Department of Justice sued a mortgage lending company, notably in defense of the Black population, since Congress passed the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 “prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, sex, (and as amended) handicap and family status.”83 Decatur Federal violated this Act and several civil rights protections by advertising mortgage products almost exclusively to Atlanta’s white population, employing and contracting white appraisers and rarely or never contracting with Black appraisers, and enabling its predominately white account executive team to engage in discriminatory relationships with primarily white real estate agencies.84

In 1979, Decatur Federal defined its lending area to exclude 76 percent of Fulton County’s Black population by using the Southern Railway line and Georgia Railroad, historic markers used to segregate Black and white neighborhoods in the Jim Crow South. Only six percent of Decatur Federal’s 24,300 processed applications were from Black residents between 1985 and 1990. In the years 1988, 1989, and 1990, the lending company only originated three percent of home mortgage loans in Black census tracts, with the remaining 97 percent in white census tracts. Stricter underwriting standards, an outright denial of financial capital, and branch closures in majority Black neighborhoods are some of the lending company’s known tactics to carry out their discriminatory practices against Atlanta’s Black residents.85

Decatur Federal was not the sole actor hindering Black homeownership in Atlanta. Their actions were seeded by the direct enablement of state and government programs that rewarded white homeowners and penalized Black homeowners. The aftermath of these destructive policies is evidenced by the 20 percent mortgage denial rates that Black Georgians face when applying for a home loan.86 It is evidenced by the -22.2 percent average devaluation of homes in Black Atlanta neighborhoods, which is equivalent to $42,964 of unrealized home value.87 The extent of the damage done is immeasurable, but by examining lending behavior, trends in affordability, the tax code and other housing and community development policies, we may know where to position our wealth building efforts in housing.

The Legacy Continues: Housing Wealth in Atlanta

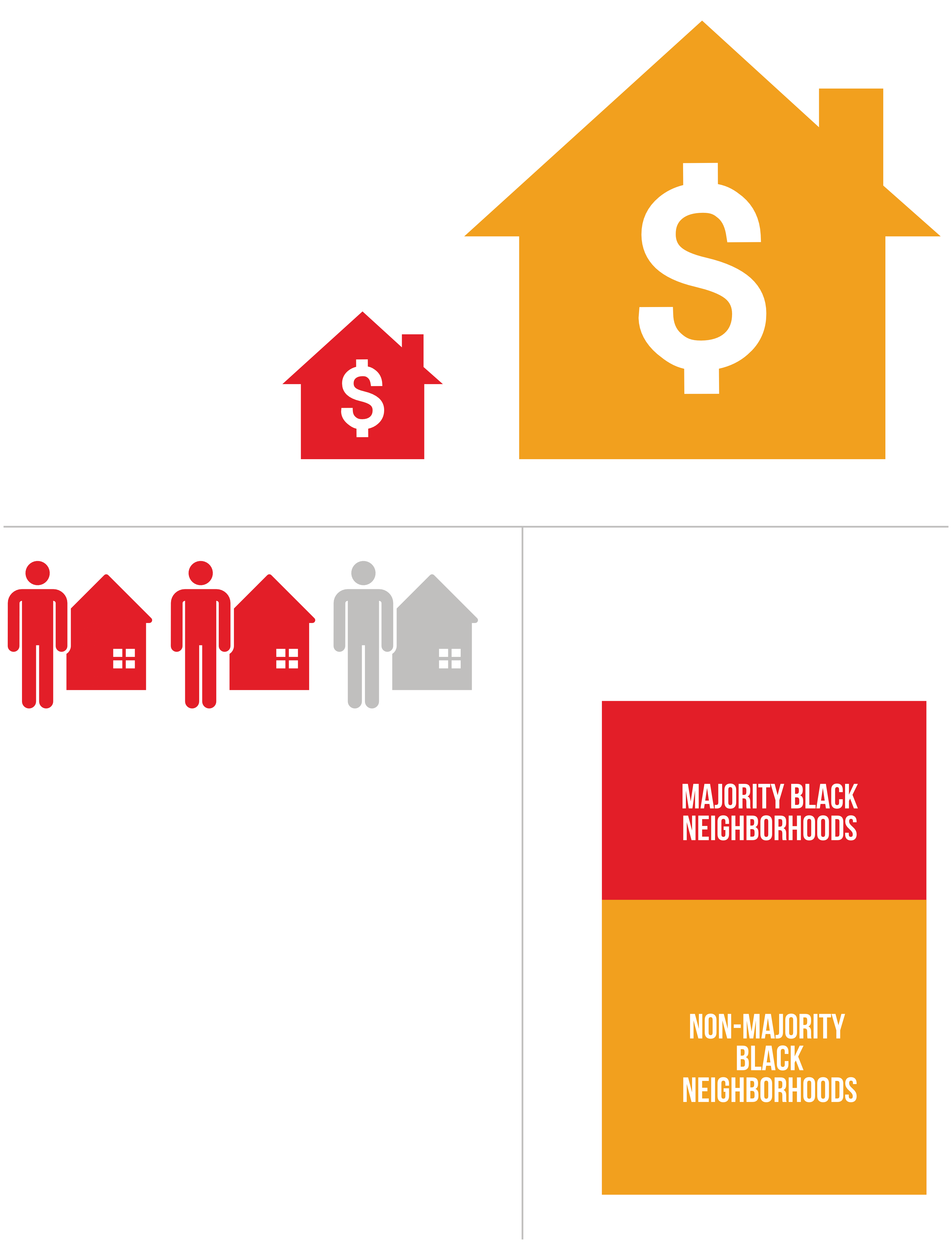

The number of mortgages originating in majority Black neighborhoods is important for examining whether access to homeownership is increasing for Black residents. Today, the rate of home loan denials in majority Black census tracts (15.9 percent) is almost double that of rates in other tracts across the city of Atlanta (8.7 percent).88 As the size of the Black population in a neighborhood increases, so does the denial rate.

The case of analysis of Decatur Federal exposed the systemic ways that Black residents of Atlanta were denied fair mortgage rates and home loan assistance. The legacy of those discriminatory actions continue to play out in the routine denial of Black borrowers seeking to purchase a home. There should be a very targeted approach to remedy these injustices. Observing the number of loans originated and loan denial rates, will offer a good proxy for measuring prejudice in majority Black Atlanta neighborhoods.

In Atlanta, Black households make up 48 percent of the city’s total households but own just 17 percent of the housing wealth, or the total value of primary residences.89 The Black homeownership rate is 33.3 percent, trailing behind the city average by 12 percentage points. The existence of this divide not only represents housing instability within the Black community, but it has direct consequences on the financial well-being and wealth building prospects of the Black Atlantans.

For those that do own their home, the benefits are not shared equitably. Homeowners face chronic devaluing of their homes as a result of implicit and explicit bias in the home appraisal process.90 The median home value in majority Black neighborhoods is $192,994, which is 2.7 times lower than the median value in majority white neighborhoods.

I know way too many families that are homeless right now and I’m talking about families, not just single people, single people with children, married people with children, and they work every day. You know what I’m saying? But they still can’t accumulate enough to make a downpayment. And then to be able to keep that you know, you got the companies taking people money out here.

Homeownership can be a meaningful wealth-building tool because it allows the homeowner to access the equity in an asset that appreciates in value. This equity affords the homeowner the ability to borrow money from their home to pursue entrepreneurial endeavors and pivot during unexpected life circumstances. But home value appreciation looks different for Black homeowners due to systemic racism. As long as this trend continues, the notion of homeownership as a wealth building tool will remain questionable, at best. As The Color of Law’s Richard Rothstein argues, “a home is one of the only assets in which the race of the owner affects the rate of return.”91

The majority of Black Atlantans are renters, so it is important to include renters in discussions about building Black wealth. When examining data at the neighborhood planning unit level, 13 out of 15 majority-Black neighborhoods have over 50 percent of occupants renting, with the average majority-Black neighborhood containing 59 percent of renters.

It is also particularly important to pay attention to the percentage of Black Atlanta residents who are cost-burdened, typically defined by spending 30 percent or more of one’s income on housing. In Atlanta, majority Black neighborhoods average 45 percent of residents classified as cost-burdened.

Cost-burdened individuals are in a reduced position to build wealth due to their overbearing housing costs. Those who are rent-burdened are in an especially precarious position with limited resources to save and consider homeownership.

The housing instability that Black Atlantans face is due to a confluence of factors. If there is any real belief that homeownership can build Black wealth, then a coordinated effort from policymakers will be needed to develop a race-conscious approach toward equity-building in the realm of housing and homeownership.

Housing Wealth By The Numbers

In Atlanta, Black households make up 48% of the city’s total households but own just 17% of the housing wealth.